Helping people see the world through each other’s eyes, overcoming personal barriers, and connecting people to prevent or resolve conflict are core propositions of participatory narrative inquiry. So it is for good reasons that conflict resolution will be the October topic in our 2018 series of monthly PNI talks. So there must be a good reason to write a blog post on this topic now. Well, there is ….

Every once in a while an article emerges that stands out. Last week that was Complicating the Narratives by veteran journalist Amanda Ripley. She describes her inquiry into the role of journalism with respect to conflict.

Maybe it is best if you read the article first, but for those who don’t, I will briefly set the scene. Amanda starts her story with what happened when Oprah Winfrey hosted an episode of the television show 60 Minutes in which 14 people – half Republican, half Democrat – were invited to talk about topics of disagreement. For example: Twitter, President Trump, health care, and the prospect of a new civil war.

The attempt failed, largely due to Winfrey’s failure to address the contradictions and thereby enrich the conversation. The result was dull and superficial television. This set Ripley off into a (re)search project ranging from soul searching to talking with diverse people whose jobs involve handling conflict. She spoke to psychologists, mediators, lawyers, rabbis, researchers of conflict, and other people who know how to disrupt toxic narratives and get people to reveal deeper truths. Probably unknowingly, Ripley did a PNI project.

Central to her story is what that all means for the journalists’ role:

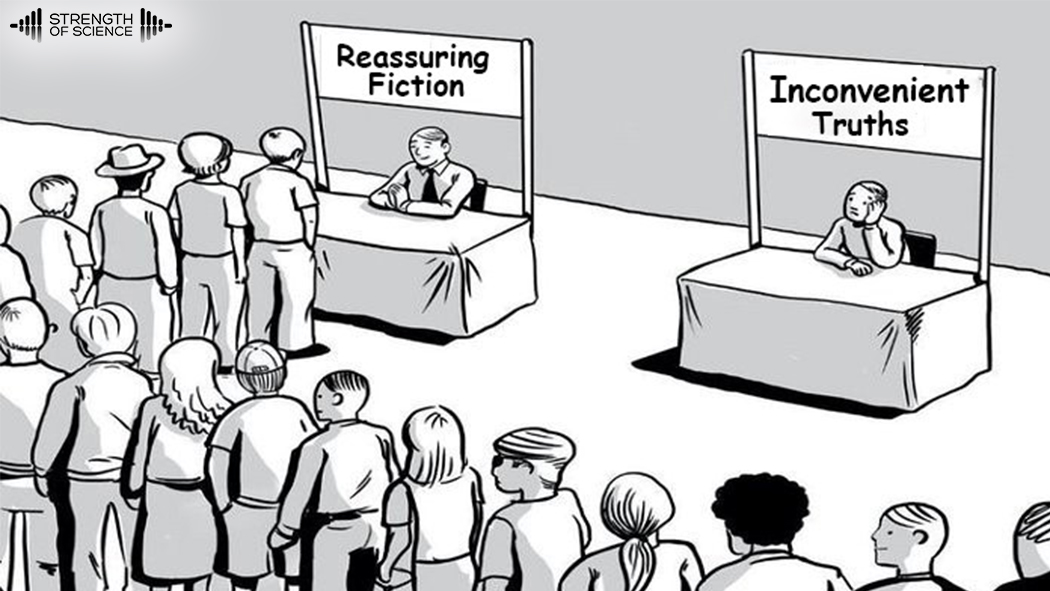

The lesson for journalists (or anyone) working amidst intractable conflict: complicate the narrative. First, complexity leads to a fuller, more accurate story. Secondly, it boosts the odds that your work will matter — particularly if it is about a polarizing issue. When people encounter complexity, they become more curious and less closed off to new information. They listen, in other words.

Complicating the narrative is – of course – something PNI excels at.

Complicating the narrative means finding and including the details that don’t fit the narrative — on purpose.

In the first half of the article, Ripley describes her voyage by citing the people she spoke to and commenting on her conversations. In her search for ways to enrich the journalist approach, she encountered ideas on how ‘intractable conflict’ emerges and how to handle it. She took 50 hours of conflict resolution courses. That opened her eyes to what she didn’t know and couldn’t do:

I’m embarrassed to admit this, but I’ve been a journalist for over 20 years, writing books and articles for Time, the Atlantic, the Wall Street Journal and all kinds of places, and I did not know these lessons. After spending more than 50 hours in training for various forms of dispute resolution, I realized that I’ve overestimated my ability to quickly understand what drives people to do what they do. I have overvalued reasoning in myself and others and undervalued pride, fear and the need to belong. I’ve been operating like an economist, in other words — an economist from the 1960s.

She also visited a Difficult Conversations Lab that studies the effect of reading prior information before entering a discussion and learned how to become a ‘conversation whisperer’. She concluded that is essential to revive complexity in a time of false simplicity. All very PNI like.

The question of course is how to revive complexity. In the second half of the article, Ripley lists six strategies journalists can use to complicate the narrative. All of these strategies feature nuance, fuel contradiction, and raise ambiguity.

The core of this article is an attempt to map these six strategies onto existing PNI practices. The article has two aims: to lay the foundation for PNI practitioners who want to reach out to journalists; and to connect to journalists who want to embrace PNI methods.

1. Amplify Contradictions

Ripley had two veteran conflict mediators watch the 60 Minutes show, and they quickly noticed that Oprah failed to respond to this comment on Donald Trump’s presidency:

Every day I love him more and more. Every single day. I still don’t like his attacks, his Twitter attacks, if you will, on other politicians. I don’t think that’s appropriate. But, at the same time, his actions speak louder than words. And I love what he’s doing to this country. Love it.

Instead of noticing and probing into the contradictory comment (love him, don’t like what he does), she quickly went on to the next participant. She failed to set a tone for complexity. She didn’t pick up and amplify the contradiction. She didn’t destabilize the narrative as an antidote to the fact that narratives tend to get skinnier when a conflict deepens and the gap widens.

Here PNI does a good job right out of the box. Whether participants are exchanging stories in a simple story circle or in one of PNI’s more complex exercises (such as building a timeline), they destabilize and complexify each other’s narratives. The simple rule “respond to a story with a story” sets the scene for amplification and diversification. Contradictions living among the participants enter into the conversation, but in a new context with different expectations. When stories answer stories, a special type of social interaction comes into play, one that people have been using to complicate their narratives for thousands of years. Story exchange is an ancient ritual whose unspoken rules create a space free of direct statements of opinion, belief, and values – and full of indirect yet revealing glimpses into the experiences and perspectives of each participant.

A PNI facilitator acts somewhat like a journalist as they introduce and shape the conversation. Elicitation questions are key to help the group start swapping stories. Framing the topic well helps people enter the area of conflict both sooner and more safely. Elicitation questions shouldn’t be biased towards any particular camp. So for example asking “Can someone share a story on why Twitter is evil?” is a poor elicitation question, while “Have you ever seen one of Donald Trump’s tweets and felt either happy or sad about it?” is better. The second question will have a better chance of evoking stories with contradictions in them, and that will give the other participants the raw material they need to complicate the narratives with their own stories.

2. Widen the Lens

Small issues in communities can explode and turn into long-lasting conflicts. The general tendency is to focus on the dispute, which usually drives it further into the extremes. In the article such a dispute is mentioned. It revolves around placing a sculpture in the city of Gloucester, which quickly develops into a NIMBY dispute. Next, the city council hires a non-profit organisation that moves in the other direction.

Instead of getting sucked into the sculpture quagmire, the group widened the lens on the dispute. They intentionally took the opportunity to start a bigger conversation — about what Gloucester wanted from its public art and how these decisions should be made.

The approach they followed was widening the topic first by inviting local experts and asking What is public art? What is included? How should we decide? Next they organized a town hall meeting, inviting citizens (100 showed up) and asking exactly the same questions of them. As a next step, they went into the neighbourhoods:

After that, organizers went out into the neighbourhoods and held still more conversations. Residents covered a huge map of Gloucester with sticky notes, marking old buildings that should be renovated; statues that had been forgotten; and locations where new works might go.

This way the feud became an inquiry — in a way that made the story more interesting, not less. The sculpture never did get installed. But later that year, the Gloucester Daily Times ran a different kind of article — focused on the city’s quest for a new arts policy.

The widening approach of involving the experts and the community is also integral to PNI. It works at all three levels of a community or organisation at once: at the macro level (top-down), at the micro level (bottom-up), and at the meso level (in the middle distance). It does this by including everyone in the project, from corporate executives to middle-level managers to employees to customers, and from town council members to public employees to prominent business leaders to every citizen. Everyone has stories to tell, and everyone needs to hear the stories others have to tell. Getting the stories to where they need to go is what makes PNI work.

Also notice something else Amanda Ripley said in that last quote: that Gloucester’s feud became an inquiry.

Sometimes people ask why we need the word “inquiry” in the name “participatory narrative inquiry.” They ask why we don’t just call it “participatory narrative.” We’ve thought about this, and we think that last word is a big part of what makes PNI what it is. Helping people share stories without any other goal can indeed strengthen communities, and it is often a beneficial side effect (and pleasant surprise) in PNI projects. But the spirit of inquiry – the challenge of discovery, the goal of seeing further than you did when you started – is central to PNI. Why? Because when that spirit is missing, the community or organisation tends to end up where it started, and PNI can do more than that. PNI’s central goal is help communities and organisations move themselves to better places than they are in now. To do that, people need to learn and explore – and inquire.

3. Ask Questions that Get to People’s Motivations

Where amplifying contradiction and widening the lens are in the ball park of PNI, asking questions is definitely in the Centre Court. Asking questions about stories after they are told does several things for participants and for the community:

- Asking questions about stories gives participants a chance to reflect on and make sense of their own stories, providing them with insights they can use to meet their own challenges.

- Asking questions about stories invites people to become co-inquirers, exploring the topic of concern by making sense of their own experiences alongside those of others.

- Asking questions about stories conveys a feeling of respectful listening and attention, which helps people to feel that their voices have been heard and valued. Indeed, when we ask people questions about their stories, we are mimicking what people naturally do in conversation to show their gratitude for the sharing and to show interest in the storyteller’s experiences and feelings. This gesture of respect encourages people to participate further in the project, whether it is a one-time project or a continuous effort.

- Asking questions about stories results in answers that, when gathered together in their hundreds, reveal surprising and useful insights that benefit the whole community or organisation.

In her book Working with Stories, Cynthia describes how she changed her mind on why asking questions is so essential. She writes:

My thinking on asking questions about stories has evolved over time. At this point in the previous editions of this book I had this sentence:

You don’t have to ask people to answer any questions about the stories they have told. If you have a very small project (and you are in the group of interest so you can interpret stories directly) you may want to just collect stories and leave it at that.

I have since changed my mind about this. It was in 2010, around the time I decided on the name of participatory narrative inquiry, that I realized I had reached a tipping point on this issue. Why did I change my mind? Because I had finally seen enough differences between projects with and without reflection on the part of the storytellers. Asking people what their stories mean, and then comparing what different people say, just works too well to write it up as optional.

So this aspect of PNI, asking questions about stories, is not optional; it’s critical. I said in the earlier editions of the book, just after the “you don’t have to” section above:

However, asking people to interpret stories can be a powerful way of finding out more about their feelings and beliefs, especially if you can juxtapose many such interpretations and look for patterns in them. Stories and answers to questions about them reinforce each other and provide a richer base of meaning than either can alone.

Take out the “however,” and I would say the same thing now.

At StoryConnect, we found this out the hard way too (since 2010) – that asking questions (even just a few, maybe not the most elegant or brilliant) always helps, if only to (partly) prevent biased interpretations.

There are lots of other reasons why asking questions is beneficial. The most important (in our experience) is that it motivates people as they feel invited to share their experiences instead of being “inquired”. This helps a lot to have them share their motivations as part of the story sharing activities and when answering questions about them in story workshops, via story points or on story forms.

Some journalists are discovering this too. In the article I mentioned above, Amanda Ripley quotes another veteran journalist, Sandra McCullough, who quit journalism after 25 years to become a conflict mediator. She says:

“If I’d known then what I know now, I think I would have asked a lot more questions about conflict,” she says. This surprised me. I’d always thought journalists focused too much on conflict; wasn’t that the problem? But McCulloch says we just buzz around conflict, never getting to the heart of the matter. Our questions stay on the surface, stoking conflict like a rake but never getting to the richer soil below.

This is seems very true, but translating that insight into practice seems hard for Ripley. Just have a look at the questions she lists near the end to probe deeper into conflicts:

- What is oversimplified about this issue?

- How has this conflict affected your life?

- What do you think the other side wants?

- What’s the question nobody is asking?

- What do you and your supporters need to learn about the other side in order to understand them better?

None of these questions will elicit stories, but they are not hard to repair:

- Did you ever say to yourself “this is oversimplified”? What happened that made you think that?

- Do you recall a moment where this conflict affected your life? What happened?

- Have you ever seen somebody do or say something and said to yourself, “Oh, so that’s what the other side wants”? What happened that made you think that?

- What is the one experience you’ve had that you wish people would ask you about? What experience would you like to hear about from other people?

- If you could see into the lives of the people on the other side of this issue, what moment of their lives would you like to watch happen? When they first (or last) did or said or thought something? When something happened?

I think and suggest that journalists and PNI practitioners should cooperate in order to make progress quickly. There is one piece of advice for journalists I want to add here: start cooperating with non-journalists. Seek fruitful relations with practitioners in other fields. I believe that this will help you to complicate narratives faster.

4. Listen more, and better

Like journalism, in business and “communication” in general #storytelling has attracted the majority of attention during the last few decades. A whole industry has emerged that helps business and government actors and agents deliver their messages.

Participatory narrative inquiry recognizes the importance of storytelling, but balances it radically with #storylistening (aiding sharing) and #storywork (creating insight, making sense, taking decisions). This is important but far from easy. Thus the fourth suggestion to improve journalism applies to PNI just as well. We’ve witnessed lots of bad to very bad practices over the years and committed the crime ourselves. That – in itself – is not the problem, as long as the embarrassment rule is actively in place. This rule is described by Cynthia as:

When you are not embarrassed about your results or methods after a few months, you are not learning fast enough.

Amanda Ripley writes something similar:

Reporters rarely get trained in how to do this; we get a lot of feedback about our stories from editors and readers but very little about our methods.

Next she starts a very useful discussion on how journalists can improve their methods, build trust, attend to gap words, things not said, signposts and ways to double check all this. Very useful stuff, but not the direction I want to move to since I think there is a more important aspect that PNI can add here. Again it is about scale and continuity. Even though a project with 40 stories covering a short period of time can be extremely useful, I feel that PNI can be of tremendous value when applied over time, on a bigger scale and when used to have a real impact on the public. Ripley seems to sense that too when she writes, earlier on in the article:

That means they have to shift from a one-night stand business model to a long-term relationship with readers

How to do that? Well, here is a suggestion. At StoryConnect we have had a pending application on our shelves for a couple of years. Its name is ReaderResearch and it enables (investigation/research) journalists to engage with their readers on an unprecedented scale and depth. Topics can be the same as mentioned earlier, but also include commercial / governmental research challenges such as involving the public in evaluation of policies or creating options with the public/readers.

ReaderResearch is an 8-step process that starts with an article wherein the journalist explains to readers what the problem/challenge is and why they need help (knowledge) from the readers. Next, readers can start sharing stories via a simple StoryPoint and these responses are used not only to write the 2nd article asking more specific responses, but are also used to create a better StoryPoint that features much more powerful elicitation questions and questions about the stories.

Over the course of the 8 articles the focus gradually moves from collecting to making sense of (ideally with readers) and finally to writing classical journalist articles. The latter are deeply informed by the PNI results of course.

I think that this way of implementing the “humans need to be heard before they will listen” truism provides a way for journalism to improve the way it engages with society. It enables them to move away from staying at the sidelines and move towards facilitating the emergence of novel solutions, without losing their independent role. I think ReaderResearch is a good example of moving from a dialogic to a trialogic mode of discussion. It moves far beyond the Hearken solution. (More on that in a later blog.)

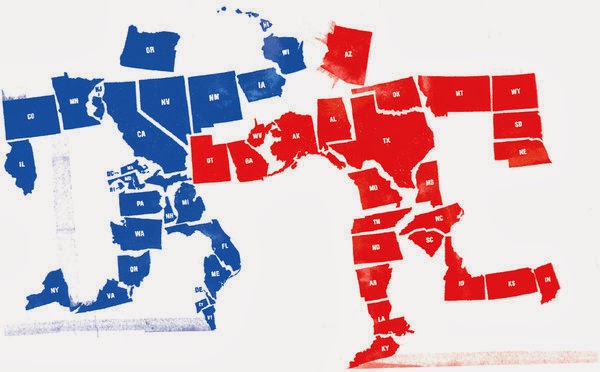

5. Expose People to the Other Tribe

Amanda’s suggestion #5 is to expose people to the other tribe. Putting aside the question of how many “tribes” actually exist, her questions are a bit shallow:

- What do you think the other community thinks of you?

- What do you think of the other community?

- What do you want the other community to know about you?

- What do you want to know about the other community?

With such questions, especially when asked online, chances are that answers will be disappointing, short, or even aggressive. It would be more powerful to have people share stories with each other. One simple example:

- Is there a moment you can recall that you wish you could tell people from the other community about? What happened in that moment, and what would you like to tell people about what that moment means to you?

Next one can ask questions about the opinions, beliefs, and values embedded in that story. Critically, those questions will be about the story, not about the person who told it. That’s one of the reasons we tell stories: to create some space between our experiences and our identities. If I tell you about something that happened to me, you and I both know that I am in the story, but you are more likely to ask me questions about the story than you are to sidestep the story and come straight at me. A story is a negotiating device, a way to talk about dangerous topics with some rules that keep the interaction in a safer place for everyone involved.

In a PNI project, answers to questions about stories can be used to actively stimulate tribes by reading stories and comparing patterns from other tribes. For example, one could publish articles with such stories in them in the preferred news channels of various tribes. This way people would be exposed to the experiences and perspectives of others and safely learn to see the world through their eyes. Journalists have been doing this for centuries, but PNI can help them increase the scope and depth of exposure.

6. Counter Confirmation Bias (Carefully)

Finally, suggestion #6 is about countering confirmation bias. This idea describes using surprising sources from within the tribe, increasing the use of visuals, and stating facts rather than negating false beliefs. The nice thing is that PNI, done well, and provided narratives are gathered form a wide variety of perspectives, provides all of these qualities automatically:

- Use surprising sources. Encountering stories from within and outside one’s tribe is almost guaranteed to have a surprising effect. As we have seen many times, every well planned PNI project is full of surprises, for both participants and facilitators.

- Increase the use of visuals. PNI does this in two ways.

- In a PNI sensemaking session, participants build visually memorable and meaningful constructions. Some examples are timelines, landscapes, and story elements. Such constructions are built of stories, or elements found in stories, or answers to questions about stories. Such constructions often become touchstones for later discussion and exploration, even sometimes entering into the culture of the community or organisation and helping to shape its norms and values.

- An optional element of PNI is narrative catalysis, a process in which a person or group carefully looks through the collected stories and answers to questions in search of useful patterns, which are used to spur thought and discussion in sensemaking. We call the process “catalysis” because it speeds up and expands the sensemaking process. The patterns in a catalysis report are rendered in visually compelling diagrams that help people discover doubt and curiosity about assumptions they never thought to question before.

- State facts, don’t negate false beliefs. The strength of participatory narrative inquiry lies in juxtaposition, not negation. For example, a group might place a collection of stories told by people with a range of beliefs into a space based on their interpretation of the way the storytellers framed something in their stories: responsible citizenship, or government aid, or heroism, or some other important thing. By doing this, none of the beliefs expressed in those stories are being negated – but they are being explored and discussed. Even in a catalysis report, the rule of generating at least two competing interpretations of each pattern avoids discounting any perspectives on what the stories or the patterns mean.

(By the way, do you know how recently that whole red-state-blue-state thing arose? Look it up. You might be surprised. That’s an excellent example of confirmation bias at work.)

Breaking Building the narrative

The article ends with a paragraph titled “Breaking the Narrative”. I’m pretty sure the intentions are good here, but I’d like to take the liberty to change the title to include the word “Building”. To illustrate why, first a quote from Senator Marco Rubio in the article:

We are a nation of people that no longer speak to each other. We are a nation of people who have stopped being friends with people because [of whom] they voted for in the last election,” he said. “We’re a nation of people that have isolated ourselves politically and to a point where discussions like this have become very difficult.”

I don’t live in the US and so I can’t judge from recent experience what it is to live in a country which such deep divisions. All I know is that to break a stone one needs fine cracks, a build up of water, freezing, small plants that grow in the cracks, and so on. Breaking is done by building a crack.

I think PNI – in the same vein – can be used to – slowly but surely – build up new narratives that gradually eat away the old conflicted narratives. As such, PNI enables a transformative approach where novel narratives emerge in-between the existing ones, gradually weakening them and growing to maturity. With that ecological metaphor I want to inspire readers to start using PNI to help resolve conflicts – either in the realm of journalism or elsewhere.

Postscript

Cynthia Kurtz helped a lot with this post. Apart from correcting Dunglish sentences, she augmented a lot of paragraphs, added details and expanded some sections with key PNI basics and perspectives. So thanks Cynthia for making this a better post.

Just like the narratives and the use of parables in the Jewish rabbinical method of seeking truth through story telling, by asking a question with a question to discern the truth is a powerful method in engaging the issue of truth versus falsehood.